In the previous post, I wrote about being addicted to perfect conditions; that’s an obstacle I’ve personally faced in some of my fitness goals—to only be motivated to try my hardest when all the conditions are optimal, so I can “take advantage of the opportunity” to perform at my very best. But some people have the opposite problem. They only feel motivated when the circumstances are stacked against them.

I can kind of rationalize how this works. It’s the underdog narrative. We love a good underdog story, and in practice some people cannot find the motivation to try hard unless they see themselves as disadvantaged in some way.

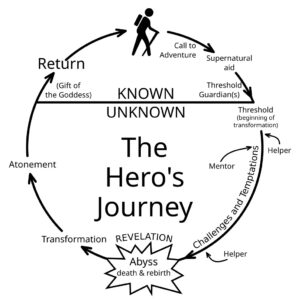

The hero’s journey

The rise of the underdog is such a common trope that we mostly take it for granted. The hero’s journey, the essential narrative template of Western (and a lot of non-Western) literature, is an underdog story—if you focus on the “challenges → abyss → death & rebirth” part.

The hero’s journey is so baked into our culture through our popular works of fiction that it can be hard to imagine a compelling story without it. Is that because it’s really the perfect formula to make a story resonate with human minds? Or is it arbitrary—we like the hero’s journey because we were raised on those stories and they shaped our ideas of what makes a good story? It doesn’t matter; this post is not about figuring out literature, but about being productive in real life.

What works in a compelling heroic fiction is not necessarily what works in real life. Imagine a story where the hero is able to meticulously prepare for the big battle, fixing all the circumstances to be in his favor, planning for every contingency, and then the battle happens and it’s not even all that challenging. Not a great story! But he wins. Those who are addicted to imperfect conditions need to ask themselves, “Am I trying to create a compelling narrative where the hero overcomes daunting odds, or am I trying to win?”

The heroic fiction often depicts all the planning and training steps as a montage. It does this because it’s boring otherwise. But in real life most of the winning is in preparation—the repetitive drudgery that creates the ideal conditions for success.

Then later, the heroic fiction throws a wrench into the hero’s plan at the last minute, because that creates drama. Do you want drama, or do you want to win? Become comfortable with the fact that most wins do not look like popular heroic fiction.

Self-sabotage

Those who can only find motivation when they’re the underdog will sometimes make themselves the underdog, just to be able to enjoy the pursuit of greatness. They’ll throw the wrench into their own training/plan/effort, because they experience that as a relieving of pressure.

It doesn’t need to be as on-the-nose as a drug binge. It could be failing to get enough sleep while you’re training, or failing to rest an injury, or refusing to think about and plan for a future goal. Then when the moment of opportunity comes, the deck is all stacked against you, and you try to make up for it with raw white-knuckled effort.

When you self-sabotage, the only two possible outcomes are that you win—and you do it in a “heroic” (underdog) way—, or you lose in a way that “makes sense” and leaves open the possibility that you could’ve won, so you don’t risk hurting your ego. All of this is a twisted mind game that feels necessary from the inside but looks very silly from the outside.

Outcome rewards

The antidote to being addicted to perfect conditions was to reward the effort, not the outcome. Conversely, the antidote to being addicted to imperfect conditions is to base your reward more on the outcomes! Fix your attention on the end result of your efforts: the sum of all your preparation and planning and self-maintenance and your final in-the-moment heroic effort.

(Same as in the last post: A “reward” could just be an internal feeling of satisfaction, or it could be something tangible you do for yourself.)

Shifting the reward structure to outcomes will motivate you to add the boring preparatory work to your heroic effort, because you need both to maximize your chance of getting a successful outcome.

Does effort suck?

Isn’t it funny how we play these games with ourselves? Needing perfect conditions to make the effort “worth it,” or needing imperfect conditions to make the effort “necessary?” I wonder, is it just that effort sucks, and we’ll use whatever excuse we can to avoid it most of the time?

But if you’ve ever been in a “flow state” or had a goal that you completely loved and could fully commit to, you know that it can be joyful to expend high effort, even day-after-day-after-day. And a lot of specific “productivity advice,” like this post, is just not necessary when you deeply love the work you’re doing. It’s for the rest of the time, when you have work that is boring but necessary in life, or that you only partially like, or that will set you up for some later life stage where you’ll thrive. Generalists are particularly likely to have projects like this—coasting in one habit while investing heavily in another; feeling their passions shift around over time. The right amount of structure and “productivity advice” gives you control over all this, so you don’t end up wasting effort on all the task-switching.

Related: here’s my growing list of Generalist productivity skills.