Prefer to listen? This article comes with custom narration by professional voice actor Alexei Sebastian Cifrese.

You should have a handle on philosophy. I’m not saying everybody should be studying philosophy. I’m almost saying the complete opposite. What everybody needs, most of all, is the ability to reject “bad philosophy.” But the act of rejecting bad philosophy is philosophy itself—it’s annoying like that.

This post is a component of the Necessary generalists theme, which says that there are some fields of study where pretty much everybody should have competence (such as philosophy/worldview). We are actually forced to be generalists when it comes to these things.

Hazards

Let’s say that any given school of philosophy might be the “right” one, the one that drastically improves your life, or your mental state, or your relationship to the universe, if you take the time to study it and internalize its values and ways of understanding the world.

That would mean every other philosophy is a non-optimal use of your time at best, or harmful to your life at worst. Somewhere in between are the philosophies that give you license to live however you’re already living, but with an excuse to be more pompous about it.

And aside from all that, there are all the philosophical-seeming arguments made by people who are just trying to get something out of you: maybe your attention, maybe a donation to their campaign, maybe your participation in a cult. Every bad idea can find a way to appeal to your sense of reason, your sense of “right thought,” your “love of wisdom.”

That’s part of memetic fitness: what qualities does an idea need to have in order to “win you over” and take up residence in your mind? There are the qualities you’d want it to have, like “being true” and “being useful,” but then there’s a range of other qualities that could give the idea a backdoor into your mind, like “having social approval,” “boosting my ego,” “hiding unpleasant emotions,” etc. And some of those are arguably still good for you on the whole, even if you don’t know the mechanism by which they’re helping you!

But the work of trying to figure any of this out is the work of philosophy, and so here we are.

Is this lindy?

“Why do I have to figure it all out? My mind has evolved to accept some kinds of ideas and reject others—it’s like I have a natural memetic immune system. It worked well enough for my ancestors, so why do I need to meddle with it?” It’s true, philosophy used to be handled by just a few respected leaders; a society where everyone’s a philosopher is not lindy. However, like the state of Physical health, there are many more hazards of this nature in the modern world than there were in the small provincial worlds we evolved in. Some reasons for this:

-

The Internet exposes you to a huge arena of ideas, new and old, simple and complex, all competing for your attention and belief. The arena is much larger than what you evolved to manage.

-

The Internet also allows ideas to spread much faster, increasing the rate of their evolution. New ideas can go from “weird observation” to “international viral meme” in a single afternoon. And old ideas can find new ways to appeal to your identity, as soon as some aspect of your identity gets noticed on the Internet: communism for evangelical Christians; pro-gun-ownership for black people; witchcraft for interior designers—there are refined, specialized arguments being deployed for all! So ideas are much more memetically competitive than they were before.

-

Newer ideas can benefit from the (admittedly few) things we now know about human psychology. Arguments can be designed to target the weak points of your mind, using knowledge that was gained in a clinical experiment. We did not evolve to defend against things like this.

Aside: Natural-born philosophers

If you’re an analytical thinker, or a highly verbal thinker, or you score high in Big Five openness (find out), then you probably naturally enjoy at least some form of philosophy. That doesn’t mean you love reading long tomes from the 1800s, but you engage philosophically with the world around you. Maybe there’s an anime series whose themes you often think deeply about. Maybe you love watching psychological thriller movies and then discussing the nature of reality. Maybe you’re religious and you feel it’s important to go deep into the theology of your religion.

You likely enjoy considering new beliefs and values, even if they feel weird at first, because they just might be right! Thus you’re extra vulnerable to being changed by ideas, which can be good or bad. So if you’re a natural-born philosopher, your philosophical self-defense is even more important.

I suspect there’s heavy overlap between natural philosophers and generalists. Big Five openness, which characterizes generalists’ natural interest in new activities and goals, applies just as well to new ideas. Also, generalists juggle a variety of mindsets, purposes, and social groups: they may need an especially complex narrative structure to tie everything together—to put each thing in its proper place and make the generalist’s life a coherent story.

Go all the way through

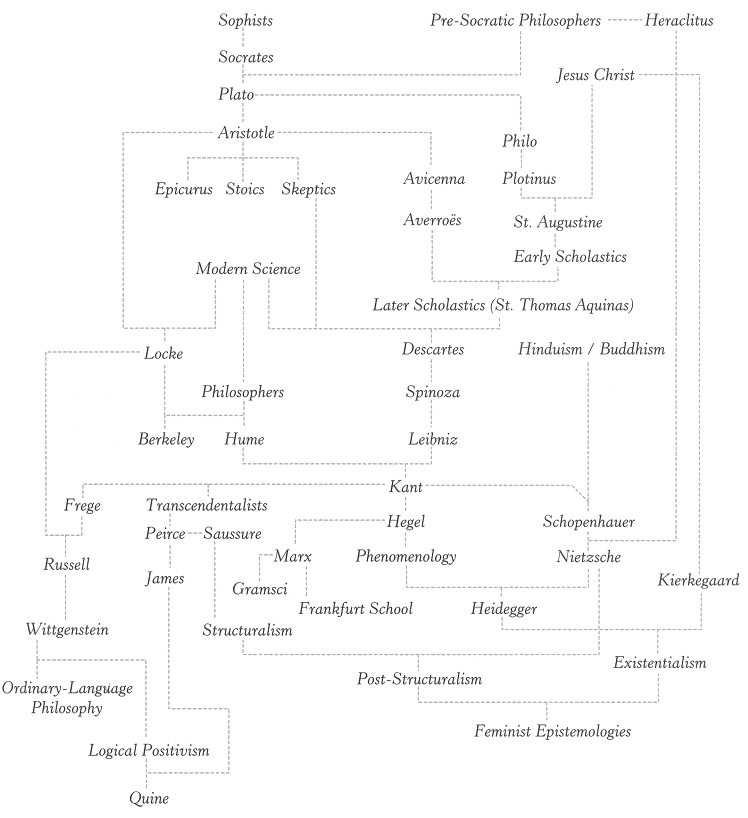

When you start to consciously dabble in philosophy, what’s most important is that you go all the way through: get familiar with a lot of different philosophies that contradict each other. Read their arguments. Get into actual arguments. Think about what makes a compelling argument. Analyze the ideas as if they were objects you’re consuming, like food. Is it palatable? Is it healthy? Use all that information to put together a healthy diet for yourself.

But don’t stop halfway. The most dangerous thing to be is a person who has studied exactly one philosophy and found it to be perfectly self-evident. That’s the “zealot” type—someone who is fully convinced of something, to the point of drastic action, but without any real examination.

I feel like most books of advice need a sort of pairing of… “OK, so, you’ve read that book, and it really helped you, and you’ve internalised and been using its lessons for a few years. Now here’s the book you need to read to undo the damage from that.”

— David R. MacIver (@DRMacIver) October 9, 2022

Another dangerous thing to be is the person who has read a little philosophy but then stopped at the “Wow, I sure feel like an intellectual” stage—the mind virus that plagues college freshmen all over the world. This person has a vague sense of intellectual prowess and then makes it a critical part of their ego. They’re a danger to themselves, because their “intellect” can be challenged and held hostage by clever arguments that will push them into extreme beliefs or actions. They’re also easily baited into online arguments, which are of questionable value. They’re the “midwit” type: they know enough philosophy to pad their ego and sound smart when describing themselves, but not enough to live a good life.

The most valuable thing you get out of reading philosophy and thinking deeply about it and trying to construct a worldview from foundations that you’re comfortable with, is that it gives you solid grounds to reject most bad philosophy, sneaky arguments, etc. When you’re all the way through, then you return to a state of not constantly questioning everything. That’s the natural state of your mind, but you return to it having already questioned a great deal and adapted your worldview. Thus you return with greater stability. And that’s important, because not constantly questioning everything is required if you want to really do anything with your life.

All this is necessary: this modern world of advanced memetic competition calls for minds that have gone through the bulk of it and come out with nuanced understanding—advanced philosophical self-defense.